The Nagaika is a short whip deeply tied to Cossack life and practice. Built for practical use on horseback and in daily discipline, it served as both a working tool and a marker of readiness. Its construction, handling, and meaning developed over centuries in steppe environments where precision, resilience, and clear function shaped every object carried. In this series of writings looks at what the nagaika is, how it was made, and the roles it played across different periods of Cossack history, from the traditions that first shaped it to the hands that still carry it today.

Part 1: Nagaika in Cossack Life

Throughout a Cossack’s life, the nagaika remained a constant companion. It was placed above the cradle of a newborn boy to ward off evil spirits, a quiet blessing and a symbol of protection from the very first days of life. As a boy grew and learned to ride, a nagaika was given to him, not as a toy but as a marker of emerging responsibility. It taught early lessons about control, timing, and respect – qualities that would define adulthood as much as any weapon or oath.

Later, the nagaika travelled into battle, often secured to a saddle or worn at the wrist. In emergencies, when a rifle or sabre was lost, it served as a fast, flexible backup weapon. It was equally important on hunts, where it helped manage horses, hounds, and herds. Within the community, the nagaika enforced discipline too, not through cruelty, but as a reminder that every action carried consequences. It shaped the everyday flow of life, from family households to military patrols.

When a Cossack died, his nagaika was not left behind. Along with his shashka and bridle, it was placed beside him in the grave, recognising that the tools which served him in life belonged also to his journey into death. The whip had witnessed it all: first steps, first rides, the fires of battle, the weight of command, the bonds of brotherhood. It was never just an object. It was part of the Cossack’s way of meeting the world.

With readiness, with control, and with honour.

Part 2: From the Scythian Whip to the Nagaika

The origins of the nagaika reach far deeper into history than the rise of the Cossack hosts themselves. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when such a tool first took shape, but the idea of a short, flexible whip designed for quick control and sudden strikes belongs to a much older tradition of steppe cultures.

Two main theories attempt to explain the word nagaika. One links it to the Nogai people, a Turkic-speaking group who lived north of the Caucasus and along the lower Volga. These communities were master horsemen and cattle breeders, and their everyday tools, whips among them, naturally found their way into the wider cultures of the steppe. It is likely that contact between Cossacks and Nogai tribes, whether through conflict or alliance, left linguistic and practical traces behind. Another theory suggests a link to the Sanskrit word naga, meaning “snake,” referencing the whip’s long, braided body that coils and moves with a serpentine grace. While visually compelling, this connection is more poetic than proven.

What is clearer is that flexible, hand-held whips have been part of Eurasian warfare and pastoral life for thousands of years. Roman-era historians such as Herodotus, Pompeius Trogus, and Polyaenus describe how the Scythians, an Iranian-speaking, semi-nomadic people whose territory stretched from the Danube to the Don, returned from long campaigns only to find themselves challenged by a rebellion of their own servants. Legend tells that they defeated them not with swords, but with whips, driving them from the steppes. Whether this episode is strictly historical or mythologised, it shows how deeply associated whips were with power, control, and survival across the ancient steppe.

The Scythians themselves are often misunderstood. They were not Slavs, but an Iranian-speaking people more closely related by language to the ancestors of modern Ossetians. Their mastery of horseback warfare left a lasting influence on all later steppe cultures. Many practices, both martial and practical, filtered down through centuries, adapting to new needs and identities. In this sense, the Cossack nagaika can be seen as a distant descendant of those early tools: leaner, faster, and tuned to a new world, but carrying the same underlying spirit.

Before the nagaika took its present form, heavier weapons dominated. The kisten, a short-handled flail with a spiked or weighted ball attached by a strap, was used by Slavic warriors against armoured enemies like the Khazar Khaganate. It relied on momentum and force to break through helmets and breastplates. Alongside it appeared the shalapuga, a long, braided whip ending in a metal weight. Designed for striking lightly armoured riders, the shalapuga blurred the line between a whip and a flexible mace.

As gunpowder spread across the steppe and heavy armour fell out of use, these older tools became less practical. What survived was the principle of fast, flexible control. The nagaika grew out of that transition: lighter than the kisten, more versatile than the shalapuga, perfectly suited to a world where quick hands and sharp awareness mattered more than brute strength alone.

Part 3: Early Skills and Traditions Around the Nagaika

Even before a young Cossack could properly wield a sword or carry a rifle, he would begin learning the handling of a nagaika. It was a practical education, shaping the hand, mind, and character of the future horseman.

Boys were introduced to the nagaika early, often around the age of eight. Their first lessons were simple but essential: rotating the whip smoothly, feeling its weight and momentum, and guiding its movements with the wrist rather than the whole arm. There was no room for careless movement. Every strike, every flick of the leather, needed to be deliberate. Early mastery of the nagaika laid the foundation for everything that came later – riding, fighting, commanding.

Training was always done with eyes wide open. This wasn’t about watching the whip like a hawk, but developing full-body awareness, tracking motion by feel and instinct. A boy who could control his nagaika without flinching or losing rhythm carried that steadiness into the saddle, the skirmish line, and the long rides across uncertain country.

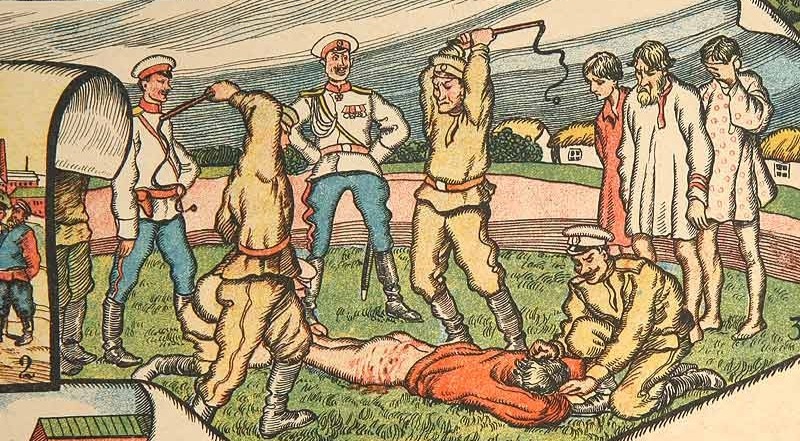

The whip’s role extended beyond training and ceremony. Within Cossack communities, the nagaika also served as a tool of discipline, swift, public, and sharp when needed. Minor infractions were corrected with a quick, controlled strike, meant as a reminder without lasting harm. For more serious offences, traditional punishments could involve formal ceremonies of public correction. One of the most severe, known as “to be run through the Cossack line” (прогнать через казачий строй), required the offender to pass between two rows of fellow Cossacks, each armed with a nagaika. As the man passed, each Cossack delivered a measured strike. It was a harsh but structured ritual, meant to punish, humble, and ultimately reintegrate the offender without permanent exclusion.

Ceremonial uses ran just as deep. In many Cossack communities, a man not born into the host could still earn a place through rites of acceptance. As part of the ceremony, the candidate stood before the elders, demonstrating knowledge of Cossack prayers, customs, and codes of honour. If judged worthy, he was struck three times on the back with a nagaika by the ataman: once for faith, once for homeland, once for honour. These were not blows of punishment, but a physical pledge to his new responsibilities.

In daily life, the whip was never far. Looping from the wrist while riding, tucked into a boot when walking, ready in times of need. In peace, it guided horses and herded livestock; in tense moments, it corrected missteps quickly and with restraint; in emergencies, it became a tool of sudden disruption – hooking reins, knocking hands from hilts, creating space without violence.

Even now, traditional nagaikas are still made and carried by those who keep the memory of Cossack ways alive. Whether displayed with pride, used in ceremony, or practised as a living skill, the nagaika remains a symbol of readiness and mastery.

Part 4: The Nagaika as Martial Art and Discipline

Over time, the nagaika became more than just a tool or ritual object. It developed into a system of movement and training in its own right, blending physical skill with mental and bodily discipline. Across different periods, under Cossack hosts, in Imperial service, through Soviet suppression, and into the modern era, the nagaika remained a living practice, evolving with the world around it.

During the period of Imperial Russia, the nagaika was carried not only by individual Cossacks but by mounted units and irregular cavalry forces integrated into the Tsar’s armies. Cossack regiments were famous for their mobility and shock tactics, and the nagaika was often used in situations where a sabre or rifle would have been too lethal or too cumbersome. In close crowd work, patrols, or managing prisoners, a strike from a nagaika delivered sharp pain and clear command without necessarily causing permanent injury.

Mounted police and gendarme units used it as a non-lethal control tool during riots or public disturbances, particularly across the vast rural stretches of the Empire, where firearms were not the first resort. The whip’s speed, precision, and psychological impact made it highly effective at creating order, or at least enough hesitation to allow forces to move or separate crowds without escalation.

After the revolutions of the early twentieth century, as the old Cossack hosts were dismantled and many traditional practices were suppressed or displaced, the nagaika nearly disappeared from formal public life. Yet it survived in small pockets, carried by tradition, by groups of martial arts practitioners, or by those who understood that a living culture is not easily lost.

In the post-Soviet years, the nagaika saw a revival, not just as a cultural symbol but as a martial art in its own right. Modern training systems emerged, treating the nagaika as a serious discipline requiring coordination, timing, spatial awareness, and controlled application of force. Schools in regions like the Don, Kuban, and Ural, as well as in urban centres, began offering structured training in handling, strikes, deflections, disarms, and even breathing techniques integrated with whip movement. Some systems blend historical techniques with principles borrowed from other martial arts, such as rhythm training from sword schools, or footwork from folk wrestling.

Beyond martial use, the nagaika found a second life in the world of therapeutic and bodywork practices. In some communities, lightly applied nagaika strikes, carefully controlled and directed, are used as part of massage therapy sessions. Practitioners believe that the rhythmic tapping and sweeping motions of the whip help to stimulate circulation, release muscle tension, and support the nervous system’s natural processes of relaxation and recalibration. This form of therapy is still relatively niche but growing among those interested in combining traditional physical methods with modern holistic health approaches. Here, the whip is not a weapon or a punishment, but a tool linking physical sensation and emotional grounding.

In some training circles, the nagaika has even been incorporated into breathwork and meditative practice. Exercises using slow, deliberate whip movements, coordinated with controlled breathing patterns, teach practitioners to regulate stress responses, develop sharper focus, and move from a state of reactive tension toward a more fluid, responsive presence.

Part 5: Varieties of Nagaikas

As the nagaika became an established part of Cossack life, different regions and hosts adapted its design to meet their specific needs. Although the basic idea remained the same – a short, flexible whip, quick to deploy and easy to carry, the details of construction, balance, and handling varied across time and geography.

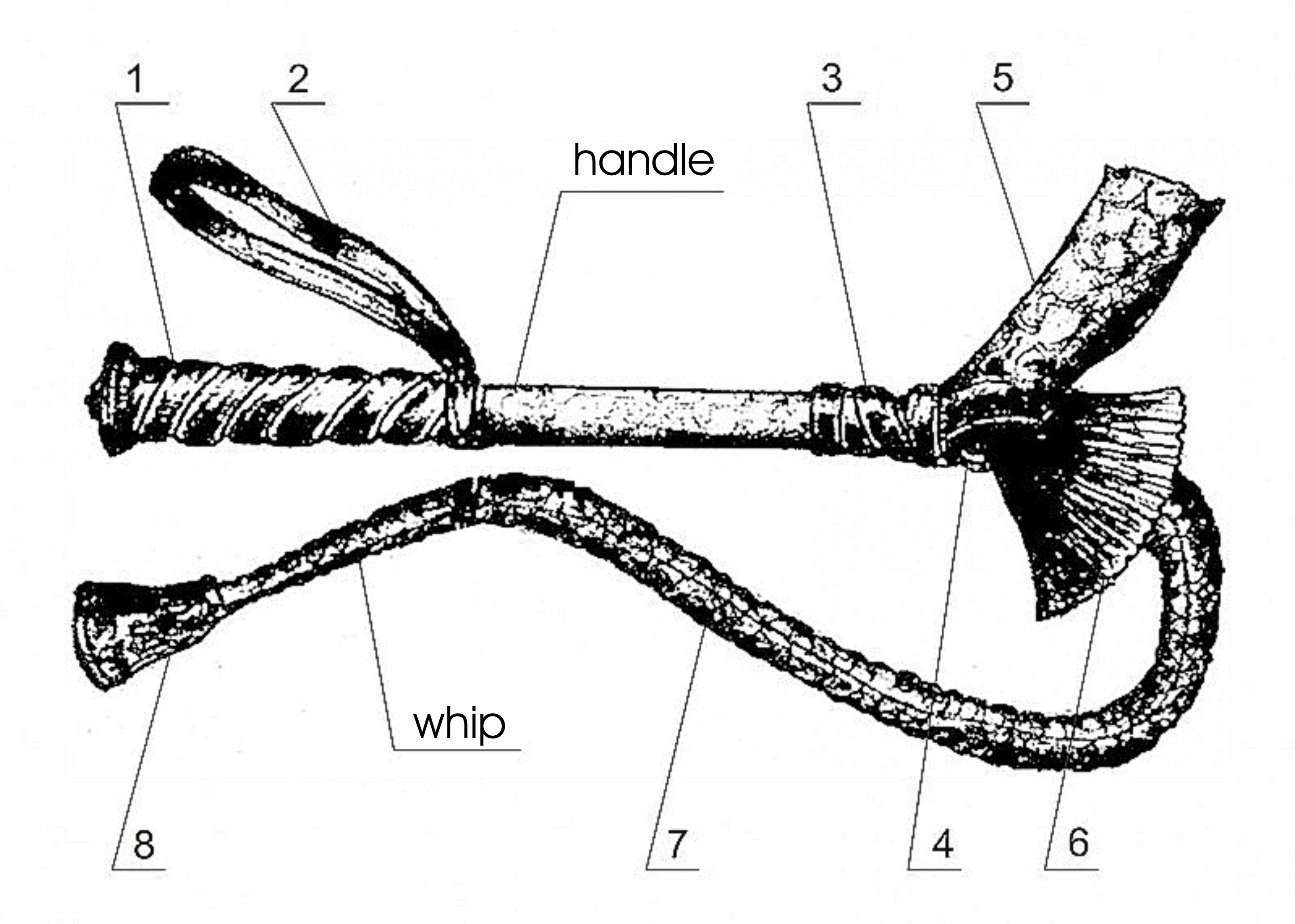

A traditional nagaika was used for controlling and training horses, as a weapon, and also for performing sporting exercises (flanking/flourishing). The main elements of the nagaika are:• A handle measuring 30–40 cm, usually made of natural wood and covered in leather.• The body itself, around 50–80 cm long, made from braided leather strips that thicken toward the middle.

Most Common Types of Nagaikas:

• Don Nagaika

A traditional Don nagaika had a rigid wooden handle measuring about thirty to forty centimetres, connected to the whip body by strong leather loops or metal rings. It is distinguished by its simple construction and unique braiding and was typically carried by the horsemen of the lower Don region. The Don style favoured sweeping arcs and rotational strikes, particularly suited to mounted use where reach and wide field control were essential.

• Kuban Nagaika

By contrast, the Kuban nagaika, common among Cossacks further south, was shorter, lighter, and more tightly integrated. Its whip was braided directly into the handle, without any mechanical separation, giving the impression of a single seamless extension from hand to tip, favouring quick, snapping motions rather than broad swings. It responded rapidly to changes in wrist motion, making it an ideal tool for close-quarters riding and quick corrections on the ground.

• Ural Nagaika

The Ural nagaika, found further east, blended features of both. Structurally similar to the Kuban style, it often included a heavier pommel at the end of the handle, shifting the balance slightly. This weight allowed the user to generate more momentum during swings without sacrificing the quick handling that defined the lighter styles.

• Knut

The Knut was heavier and thicker, with a round cross-section. Models with a metal tip were used for corporal punishment, maintaining public order, and protection from wolves.

• Duraka

The Duraka was typically twice as thick as a standard Cossack nagaika, with a heavier and thicker tip. This type was used for defense against wild animals, crowd control and attacking enemies in battle.

• Arapnik (leather or rope whip)

The Arapnik, favoured in hunting and animal handling, was longer still, with a more rope-like body and a small, weighted slapper or a simple thread cracker at the tip.

Other variations appeared as well. The Tatar kamcha, long and thin, was closely linked to Don traditions but reflected different stylistic needs. The Volchatka, or “wolf-slayer,” had a denser braid and often a reinforced tip, designed for hard strikes against predators during dangerous hunts on horseback.

The broader history of the steppe shows that the nagaika was not an isolated invention. Many nomadic cultures like Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Mongol, carried short whips of remarkably similar construction: leather braided around a flexible core, with short handles for rapid use from the saddle. These tools served many of the same functions: controlling herds, signalling across distance, defending oneself with sudden, non-lethal force.

What distinguished the nagaika was how deeply it became woven into the living fabric of daily life, ritual, honour and identity, and became as much a symbol as a tool.

The nagaika may appear simple at first glance, but its construction requires precision, balance, and an understanding of how tension and motion interact. Every element, from the type of wood chosen for the handle to the way the leather strips are braided, contributes to how the whip moves, responds, and endures.

Traditionally, the nagaika consists of two main parts: the handle and the whip itself. The handle is carved from a tough hardwood such as birch, oak, ash, or hornbeam. It needs to be light enough for fast handling but sturdy enough to resist shocks and pulls.

Construction

1. Grip (Khvat):

the section of the handle gripped directly by the palm, usually covered with a leather wrap.

2. Wrist Loop (Temlyak):

a loop for passing over the wrist. Designed to keep the nagaika secured to the hand at all times, sometimes hooked over the little finger.

3. Fastening Wrap (Ukrep):

joins the handle to the whip—a leather strap wrapped around the handle shaft to secure the connector ring and dolon’.

4. Connector Ring (Zatsep):

the part that links the handle to the whip—a metal ring through which a matching ring on the end of the whip is threaded.

5. Flap (Dolon’):

a leather flap, narrow at the bottom (about half the diameter of the handle) and widening toward the top, designed to protect the horse from being struck by the nagaika’s metal parts.

6. Fringe (Makhra):

a thick fringe made of thin leather strips located near the top of the whip. Originally decorative or symbolic, it imitates the horsehair tufts on a traditional standard (bunchuk).

7. Braid (Sarven’):

the leather braiding of the striking part—strips woven in various patterns around the central core cord (viten’).

8. Slapper (Shlepok):

the tip of the whip’s striking part—a small leather pouch into which a weight is placed to increase the force of the blow (evolved from the striking head of the kisten).

9. Loop Assembly (Oboymitsa):

consists of the wrist loop and the securing loop.

10. Securing Loop (Zavod):

a small loop designed for threading the whip.

11. End Cap (Shalyga):

a metal sleeve fitted onto the end of the handle (used for striking with the reverse side of the nagaika).

Sometimes this part contains the end of a small knife (zalizka) stored inside the handle like a case.

• Handle length / whip length ratio: ~1–1.5 to 2.• Handle length: 30–40 cm (measured from the elbow fold to the middle of the palm).• Thickness: sized to fit the user’s hand.• Whip length: 45–55 cm (measured with the arm extended forward and slightly bent (handle vertical) the whip should not reach your body during rotation).

The Kuban type of nagaika differs from the Don type by having a shorter handle (15–20 cm) and a different method of whip attachment—the handle appears to braid seamlessly into the whip, with no visible end to the handle or clear start to the whip itself. The ratio of handle length to whip length is about 1 to 3–4.

The craftsmanship involved in making a good nagaika is subtle but essential. Every aspect, handle balance, braid tension, leather conditioning – affects how the whip behaves. A well-made nagaika feels alive in the hand: responsive, supple, and ready to obey even the smallest shift of the wrist or fingers.

Leather and Braiding

Behind every good nagaika lies the quiet skill of leather preparation and braiding. While the finished whip might look clean and effortless, its strength and responsiveness come from work done long before the first strike is ever thrown.

Cossack craftsmen traditionally used rawhide, most often cowhide, for nagaika construction. Rawhide offered the perfect combination of strength and stretch once properly treated. The process began with soaking the hide in water to soften it, making it easier to cut into long, even strips. Careful cutting was essential. Uneven strips would twist awkwardly in the braid, creating weak points or throwing off the whip’s balance.

Once prepared, the leather strips were either left to dry slightly for a firmer braid or kept moist for a softer, more flexible finish. The decision depended on the intended use. For combat-focused nagaikas, a tighter, firmer braid was often preferred, transmitting energy more sharply from the handle to the tip. For riding and daily work, a looser, more flowing whip made handling easier over long periods.

Several traditional braiding patterns shaped the whip’s body. The most common was the so-called “snake braid” – a tight, overlapping weave that created a flexible but strong body resembling the scaled texture of a snake’s back. Checkerboard patterns and diagonal weaves also appeared, depending on local styles and personal preference. Some braids included a core (viten’) running through the centre, usually made of twisted rawhide, hemp, or leather cord. Others relied solely on the outer layers for structure, favouring flexibility and speed over added mass.

Attention to tension during braiding mattered enormously. A whip braided too loosely would sag and lose energy. Too tight, and it would become brittle and prone to cracking over time. Good craftsmen learned to feel the right pull in their fingers, to hear the subtle sounds of leather stretching and locking into place as they worked.

Makhra, the fringe near the handle, was both decorative and practical. It allowed the user to feel the whip’s orientation during swings, even without watching it directly. And at the tip (shlepok) provided the whip’s final punctuation: a small, weighted leather pouch that, depending on its construction, could either sting sharply or deliver a more forceful knock.

The art of braiding a nagaika reflects the same principles found throughout Cossack traditions: resilience, precision, and adaptability. A whip built without care would fail when it mattered most. A whip built with discipline and understanding became a true extension of its wielder’s hand.